In general, market participants have long lauded companies that repurchase their shares. I’ve always wondered whether such praise is warranted and to what extent is a share repurchase program beneficial to the continuing shareholder. In this post, I’ll attempt to go through the positives and the negatives of this tool in returning capital to shareholders. I’ll also make use of some examples of what I believe to be effective and ineffective share repurchases.

First, we must establish when a share repurchase should take place. Stock buybacks are typically, and correctly in my opinion, from the excess cash generated by a business. There are a few options management has when it comes to making use of shareholder cash. Some considerations I found: (1) do nothing – let it grow (2) expand operations organically (3) expand operations through acquisitions (4) pay down debts (5) issue a dividend to shareholders (6) repurchase the company’s shares. All other options have their pros and cons but let’s keep the focus of this post to stock buybacks.

The preeminent argument for the use of stock buybacks is its ability to boost a company’s per-share earnings. The earnings per-share, EPS, is the company’s true bottom line when it comes to evaluating an income statement. There are really only 3 ways to increase a company’s EPS: (1) revenue growth (2) cost cutting (3) share repurchases. Buybacks can often be the best option for companies given the buyback results in lower share count. Take for example, a company whose earnings remain flat from year to year is able to repurchase half its share count. This buyback would result in the EPS doubling in the space of year, a feat that would be extremely difficult to obtain through top line performance or cost cutting. Best of all, this opportunity can arise from nothing more than inefficient pricing by market participants. I concede that this example is a bit too Pollyannaish but it does a great job illustrating the attractiveness of buybacks. Management buying back shares at prices below a conservatively estimated intrinsic value is the best implementation of stock buybacks when no better alternatives exist with shareholder cash.

So what then is the argument against buybacks? Simply put, management does not always buy shares at truly enticing share prices – failing to deliver the desired share count decrease. A buyback is truly useless if the share based compensation within the company engulfs the retired share count – leaving no effect on the share count, or worse, an increase in the share count. Often, management compensation is tied with EPS targets providing the incentive to make use of buybacks. But as noted in the second paragraph, there are other options which make more sense for respective businesses. For instance, a business may be better off reinvesting cash given that it is able to earn a return above its cost of capital.

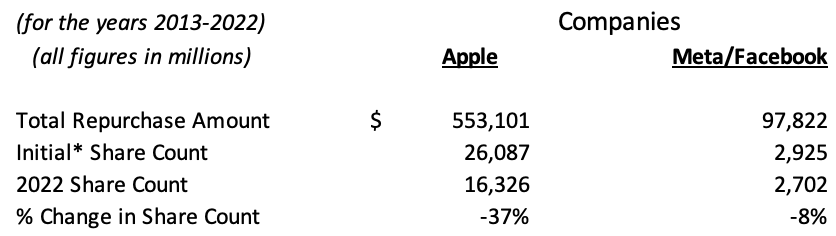

Let’s take a close look at two examples of stock buyback programs – the best and the worst of the tool in action in the past ten years (2013-2022).

First, we should examine excellent use of repurchases, best demonstrated by Apple. The company began its share repurchase program back in 2013. Since then, the company has spent a cumulative $553 billion repurchasing its shares. The share count has dropped by 37% in this time – rewarding its continuing shareholders. When buybacks are used this way, it gives the continuing shareholder a larger interest in the company’s hopefully growing cash flows. In 2021, the average repurchase price was $149, today the shares trade at $148. In this case, the price paid seems to be a nonissue. Assuming there are no other opportunities to better the company’s intrinsic value, the buyback as performed by Apple serves as a prime example of effective returning of capital to the continuing shareholder.

Moving to the uglier share repurchase program is Meta, previously Facebook. In 2017, Meta began its share repurchase program. Since then, the company has spent a cumulative $98 billion repurchasing its shares. In that time, the share count has dropped a measly 8%. An even more exasperating fact is that the average price paid for these repurchases in 2021 was $330 per-share. Today, Meta trades at roughly $180 per-share (and no, there was no stock split), representing a 45% decline. During the year 2021, Meta seems to have been lighting shareholder cash on fire under the guise of a share repurchase program all the while rewarding their CFO, David Wehner, bonuses for what was adjudged to be excellent work. In fact, from the years 2017-2021 Meta’s share repurchases only reduced the share count by a miserable 1.2%. Alas, there is some light at the end of the tunnel at Meta. In 2022, as the market reacted to a host of news surrounding the company and the share price dropped precipitously, the buybacks didn’t stop – even dipping into debt for extra liquidity. Indeed, earlier this year the company increased its share repurchase authorisation by $40 billion.

The most obvious reason as to why Apple is able to retire more of its share count than Meta can be found in their respective cash flow statements. Meta since 2017 has accumulated $40 billion in share based compensation expenses. Apple, however, has accumulated $53 billion in share based compensation expenses since 2013. While boards & managements like to reward themselves with the company’s shares, it is imperative they remain mindful of the dilution from this compensation. Meta’s buybacks have seemingly been a tool for sterilization and not the benefit of their continuing shareholders. When a buyback is used to sterilize newly issued shares, like previously at Meta, it delivers nothing to the continuing shareholder.

The examples at Meta & Apple just go to show the importance of buying back stock at attractive prices while limiting the dilution from share based compensation. If management is able to do that, the continuing shareholder will benefit and see the intrinsic value per-share grow. As noted, most management is unable to act at value-accretive prices and the equity investor should consider this. When evaluating buyback programs, it is not the dollar amount that matters but the change in share count to ensure management acts in a way that benefits continuing shareholders.

[…] Pitch Railroad Industry Primer Emirates Driving Company Pitch Discounting & M.O.S Google Pitch Share Repurchases BV v. IV Importance of Returns on Capital Activision Arbitrage? Inflation & Equity Returns […]

LikeLike