Credit Acceptance (NASDAQ: CACC) is an auto finance company that provides used-car loans to primarily subprime borrowers. Credit Acceptance’s business model deviates from the industry norm of buying loans originated from a dealer at a modest discount (although CACC does practice this under their “Purchase Loan” program). Instead, Credit Acceptance’s main focus is their Portfolio Program, where they act as an indirect lender (legally) by partnering with dealers to make the loans. Credit Acceptance sends the dealer an advance for anticipated future collections of the consumer loan. The dealer also receives a down payment from the consumer on the loan. CACC then receives 100% of the cash flow from the loan up until the amount equals that of the advance sent by CACC to the dealer plus some profit (130% of the advance – profit is called the servicing fee). After receiving the full balance, CACC and the dealer split the cash flows, typically 80-20 (20% for CACC). This works for both the dealer and CACC due to the potential profit to be made from successful consumer loans.

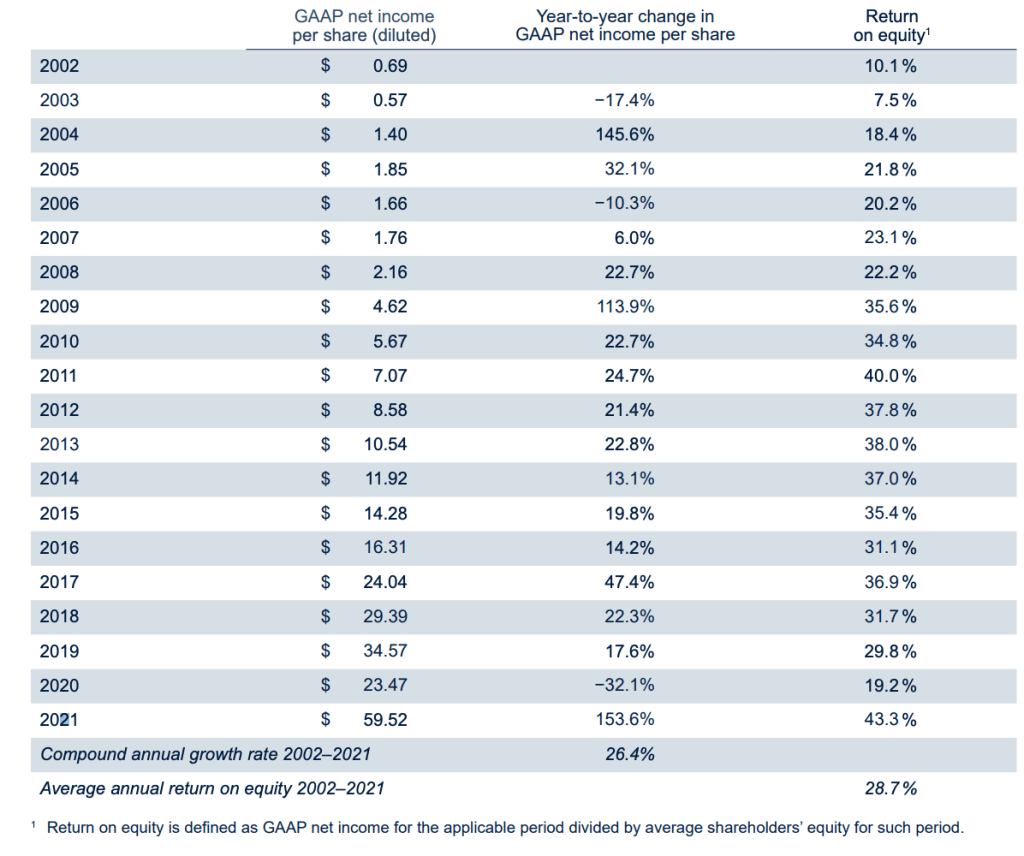

Credit Acceptance has been using this model for well over 20 years now without fail. The result from its operations have compounded diluted earnings per share at 24.9% over the past 20 years as well as an average return on equity of 28.7%.

Credit Acceptance’s Runway

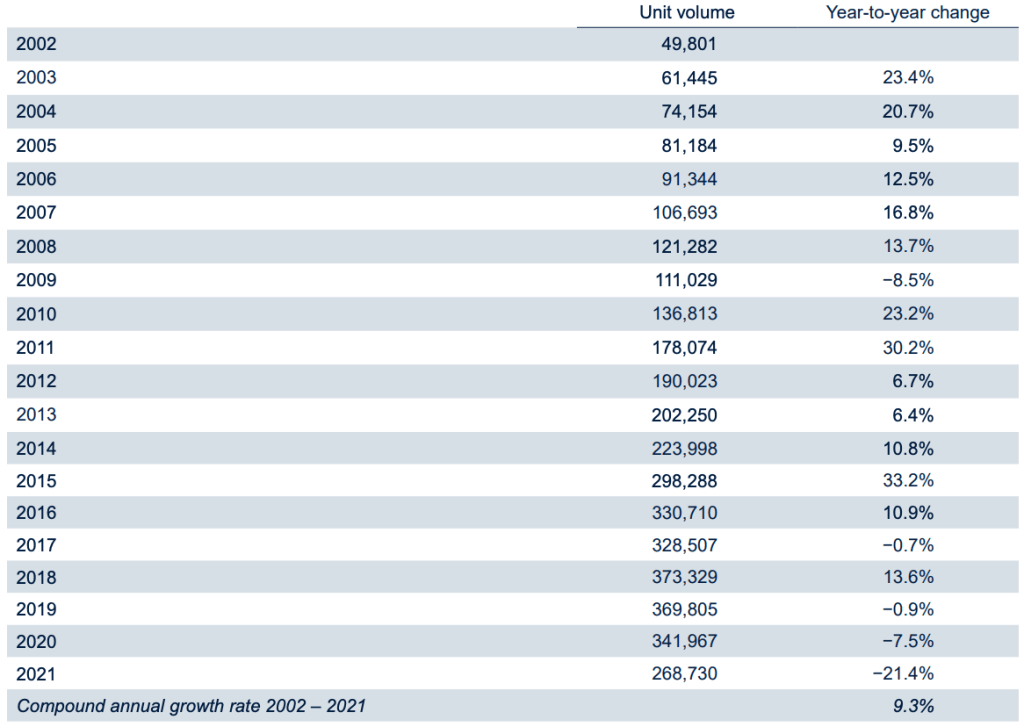

Over the past 20 years, Credit Acceptance has grown unit volume at a compounded annual rate of 9.3%. But in the past 3 years, unit volume has declined markedly. CACC already has 11,000+ dealers and with some sources estimating only 27,000 dealers in the country it will be a tough ask to expect more active dealer growth.

The past 3 years do show a potentially worrying slowdown in unit volume that could be indicative of CACC’s struggle to continuously find new dealers. Another possible explanation is the extremely loose monetary policy environment of the past couple of years. For the 3 months ended June 30, 2022, unit volume grew 5.1% vs 2021. However for the 6 months ended June 30, 2022, unit volume fell 10.5%. It is too soon to tell how the current change in interest rate policy will affect CACC but going off past cycles, there is reason to believe it will be a positive for the business. It seems that Credit Acceptance has no problem shredding some of its market share in competitive environments, knowing it will make it up when tighter monetary conditions emerge.

Business Risks

The 2 biggest risks Credit Acceptance faces are regulatory & default in my opinion. Starting with the latter, in 2021, 91% of unit consumer loans came from individuals with either no credit score or a FICO score below 650. It is difficult for many to accept a business only collecting 66.5% of their total loan value in a year.

The regulatory risk comes from moves to modify CACC by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPR). Many individuals that defaulted on their loans have sighted CACC’s high interest rates and fees to be predatory. CACC claims that their business connects those that may never have got the chance at financing to dealers that also would’ve missed out on these consumers without them. There is some truth in this claim. However, it is very difficult to claim to be benign when you charge subprime borrowers 20-30% on loans. As the CFPR and other state attorneys clash heads with CACC, the business may incur material costs or be forced to change their business model.

Conclusion

In sum, Credit Acceptance is a company that has compounded earnings at a remarkably high rate for the past decades. The company to this day still continues to return great wealth to shareholders. For the 6 months ended June 30, 2022, CACC repurchased 8% of shares outstanding, the mark of a business with excellent economics. CACC does face the problem of having very few reinvestment opportunities as seen with the shrinking unit volume per dealer count. Credit Acceptance is a business with exceptional economics but may struggle to continue compounding at such high rates well into the future.