The railroad industry is often ignored by investors for its lack of glamour. But when you ignore the narrative, you realize there is so much to learn. Not many industries can boast the operating margins the big railroads have been able to obtain over the past couple decades. I’ll attempt to tell the lengthy story of the North American freight railroad industry in this post.

History

With the passing of the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862, the US government along with Union Pacific and Central Pacific began building a railroad stretching from Sacramento to Omaha. In May 1869, the two companies met at Promontory Point, in the flatlands of Utah – marking the completion of the first transcontinental railroad.

In the late 19th-century, the railroads continued to garner greater control of transportation through consolidation. The power the railroads had led to lots of corruption in the industry and the government. The industry was rife with pools, malinvestment, and overcharging of customers. The favourable economics of the industry resulted in a number of speculative booms and inevitable busts.

Eventually, the government and the people had enough and regulation followed. In Munn v. Illinois (1877), the US Supreme Court ruled that state governments could regulate private industries deemed necessary for the ‘common good’. The ruling was later overruled in the Wabash case, where the Supreme Court found that states could not regulate interstate commerce. Down the line, the Interstate Commerce Act (1887) set up the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) as an attempt for the government to begin regulating business in the United States; ensuring railroads charged fair prices. The ICC although not completely effective did mark the beginning of the end of railroad dominance – a decade of industry decline would follow.

Theodore Roosevelt’s administration would eventually mark the end of railroad dominance in the country. The Hepburn Act passed in 1906, gave the ICC the power to regulate the maximum shipping rates. It was not unheard of at that time to set the shipping rates well below what it cost the railroads to operate. The Roosevelt administration would also bring suits against a number of big businesses at the time, earning Theodore Roosevelt the moniker ‘trust-buster’. Effective regulation would put the railroad industry into comatose for near the remainder of the century.

Revival

In 1980, with the passing of the Staggers Act, the railroads were once again free from the shackles of regulation. The Staggers Act largely allowed for the railroads to determine their own prices to compete with new modes of transport. The ICC was abolished in 1996 and has been replaced with the Surface Transport Board (STB), who are know responsible for regulation should the shippers feel hard done by. Deregulation has resuscitated the once dominant industry and the railroads have been able to invest into their operations as they see fit. Following the malaise of the 20th-century, the rails have become far more consolidated and focused on operational efficiencies and continue to be today.

Big Players:

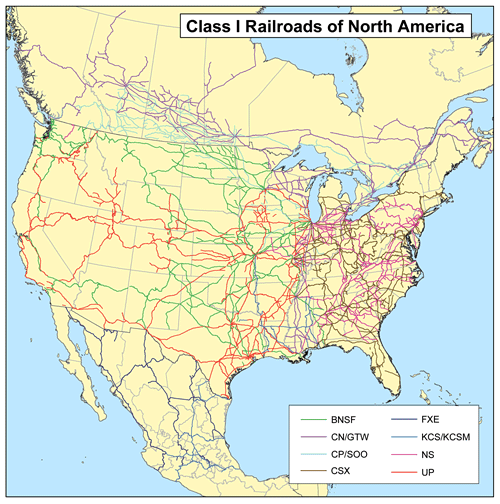

In the United States & Canada there are 6 Class 1 railroads (defined as having greater than $1B in operating revenues – adjusted for inflation yearly). The big players are broken down as follows:

Western USA: (1) Burlington Northern Santa Fe, aka BNSF (2) Union Pacific, aka UNP

Eastern USA: (3) CSX (4) Norfolk Southern, aka NS

Canadian Rails (5) Canadian National, aka CN (6) Canadian Pacific Kansas City Southern, aka CPKC

Together, the big six make up 95% of rail revenues and 75% of rail volumes.

The Assets

The rail companies are comprised of three major assets: tracks, locomotives, and railcars. The locomotives for a freight rail are often north of $3 million. While getting the right or ownership to build new tracks is nigh on impossible, if obtained, it can cost more than $1 million to build a mile of new tracks in the United States. Locomotives and railcars have useful lives well over 30 years and the land owned by railroads typically includes some amount either side of the tracks. It is all but impossible for an upstart to compete in this industry. I would go as far as saying North American rails have the largest barrier to entry of any industry, that has not been granted by their state(s).

The useful life of some of these assets also results in higher earning-to-cash conversion numbers. There is still meaningful capital expenditures required for rail maintenance but there is no need for the rails to be spending an arm and a leg for it.

Cartel-Like Economics

The big 6 Class railroads along with Ferromex (largest railroad operator in Mexico) are the parent organizations of a unique company, TTX Transportation. TTX is an off balance-sheet entity that offers railcar services to these companies, such as taking care of the railcars they leave at a destination. TTX is funded by outside investor debt, that is all but guaranteed by the big railroads. The entire purpose of TTX is to increase the margins of their parent organizations. This sounds a little like collusion to me…

Revenues

There are three main revenue sources for freight companies in North America. The three sources of revenues are as follows: bulk materials, industrial, and intermodal. The industrials segment includes plastics, metals, and ores. Bulk materials consist of grains fertilizers, and coals. The intermodal segment is the only real ‘growth’ segment and refers to the movement of containers from ships, rails, and trucks without removing content within the container. Intermodal revenues have grown in volume far more than other segments but remain a lower margin business. The revenue mix varies by company and is dependent on the geographies the tracks of the rails are located.

Precision Scheduled Railroading (PSR)

Starting in the 90s, the way rails were ran changed under Hunter Harrison (then CEO at Illinois Central) when he introduced PSR (it was really done on a large scale at CN by Harrison). PSR was a shift towards efficiency, simplifying routing networks, and improving operations. PSR moved trains into fixed schedules (similar to passenger trains), with fewer stops, less people, and longer trains – in the name of fuel-efficiency. Through PSR, the industry has moved away from unit trains (where all cars carry the same commodity) to diverse cargo being transported as needed. In the name of efficiency, PSR (& a focus on operations) has led to headcount reductions across the industry. As per the BLS, employment in the rail industry has gone from 500k (in 1980) to ~150k today.

There has been a lot of pushback to PSR from politicians, shippers, workers, and regulators. Shippers argue regulators need to do more to protect them from fees the rails charge for being off schedule. With the exception of BNSF, the Class 1 railroads have all switched to PSR. In 2019, BNSF’s Executive Chairman, Matt Rose, argued that by switching to PSR, the rails were only inviting regulatory risk – implying the margin improvement was not worth it in the long run.

There are also arguments that PSR’s cost reduction focus has contributed to inefficient safety procedures. At some rails, mechanical staff (responsible for checking on the state of the trains) have been cut and their work has been handed over to conductors – who are already slim in number. Although, it should be noted that the number of train derailments peaked in 70s and has been on a decline ever since.

Competition

The closest competition to the rails are trucks, if you would consider them as such. Rail shipping is far more cost-effective, sustainable, and speed-efficient. For all the reasons above, it simply makes the most sense for industrial economy to focus on rail transport. The location of freight customers also tends to make them captive to the railroad operating beside them, as it would not be economically feasible to use any other mode of transport. The result of this, is better economics for the railroads and returns for the shareholder.

Capital Allocation & Returns

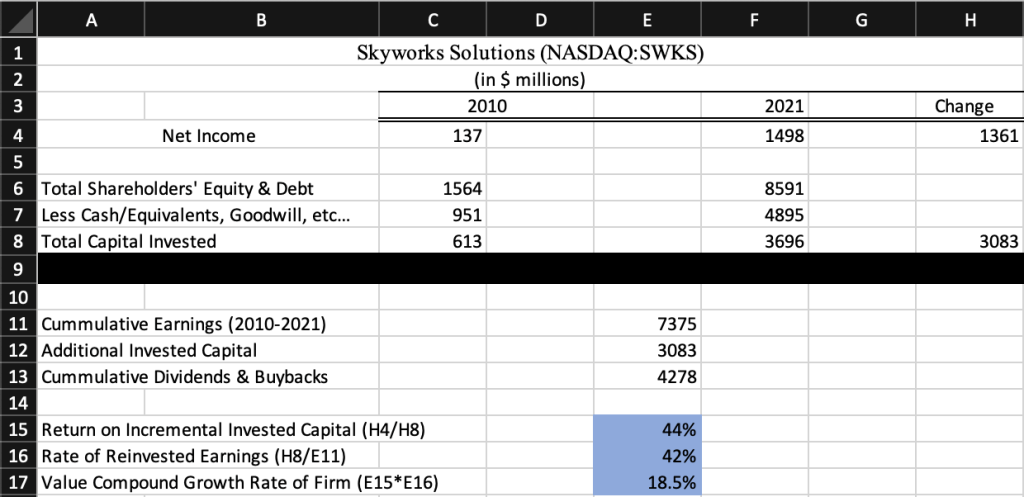

Although I have waxed lyrical about the competitive position of the big rails, they all still share one similarity – a relatively low return on invested capital. Despite being the most effective form of transport, rails do just require a lot of capital expenditures (even when minimal).

In the past two decades, there has been a focus on the shareholder at the rails. Recognizing their competitive barriers, the companies have taken on more debt to finance dividends & buybacks. The stability of their cash flows has made the decision that bit easier, returning 40%+ of free cash flow to shareholders.

In sum, using their century old barriers to entry, the railroad business looks to be economically attractive. There is decent earnings visibility, captive customers, and the ability to take on debt comfortably. This has led to railroads providing outsized returns for their shareholders through capital allocation strategies & improved operations in recent history.

Asides

(1) The rail industry has a key figure – operating ratio (1-EBIT Margin), personally not sure why EBIT margin doesn’t suffice… (2) Union Pacific bought Central Pacific, through their Southern Pacific acquisition in 1996 (3) Hunter Harrison’s effect on the railroads can’t be understated, serving as CEO at CN, CP, and CSX (4) The industry has no shortage of activist investor history: Ackman at CSX, Elliot Management at CN, and Soroban at UNP (5) Rail landownership has led to a number of different businesses sprouting from within the railroad companies (ex: SPRINT).

(6) The Credit Mobilier scandal (1865-69, exposed in 72′) highlighted the extent of corruption in the Gilded Age. Credit Mobilier was believed to be a construction contractor for Union Pacific, but was truly controlled by UNP’s management. The plot was simple, to bill UNP at rates above reality and thus the government (at the time subsidized UNP rail construction). Credit Mobilier shares were given to politicians (from Congress to the sitting VP) in exchange for silence, receiving dividends for embezzling state funds. After being exposed, a number of politicians would leave their post and Union Pacific was left on the brink of bankruptcy.