The returns on waste stocks have been attractive for many, many years. I wanted to write a bit about what I’ve learned about the industry over the past few months of studying it. The model is straightforward: companies collect waste from residential, industrial, or commercial customers and dispose of it at landfills, transfer stations, or recycling facilities (including the increasingly popular renewable natural gas facilities). They earn revenue through hauling fees, tipping fees at disposal sites, and various charges tied to handling.

Moats + Opportunities

There are obvious moats in waste management, including economies of scale, high barriers to entry from the cost of equipment and disposal assets, and customer stickiness. The benefits of scale for a waste hauler are clear. Larger companies can spread the costs of expensive infrastructure over more customers, giving them a cost advantage that smaller players cannot replicate—unless, of course, they are acquired, which is exceedingly common in the space. As the major players grow, they also benefit from improved route density and optimization, making collection routes shorter, cheaper, and more efficient, which lowers operating costs and improves margins.

Vertical integration is central to value creation in the industry. A vertically integrated operator that owns both the hauling routes and the landfill can internalize the waste it collects, dramatically reducing tipping costs and capturing the economics at every step of the chain. To illustrate, imagine a company paying $30 per ton in tipping fees at a landfill while charging customers a total haul cost of $500, which includes transportation and tipping. If that same company owned the landfill, it would eliminate those tipping fees entirely. In other words, the cash that would have been paid out flows straight to the bottom line, improving margins significantly.

There also exists a valuation gap between vertically integrated and their non-integrated counterparts to reflects this dynamic. According to an industry expert, you can expect the private market valuations of these large vertically integrated haulers to be in the high single digits, with non-integrated players seeing their multiples half of that. Landfill ownership creates a moat; the regulatory, environmental, and zoning requirements to build new disposal capacity cannot be understated. Couple this with landfill scarcity increasing further demonstrates the value of these assets. Unexpected volume increases can see the useful life of landfill assets drop faster than expected, creating a need for alternative methods of disposal (e.g., incineration, waste-to-fuel, recycling).

This is driving investment into recycling infrastructure, material recovery facilities, renewable natural gas projects, and waste separation technologies. These initiatives are not just about environmental compliance; they are increasingly tied to economics. Rising values for recycled materials, such as OCC (old corrugated containers), and regulatory incentives like renewable identification numbers (RINs) generated through RNG projects are creating new avenues for margin expansion. The waste majors understand this and have already begun taking steps in this direction, as seen with WCN’s New Ridge RNG plant.

Valuations

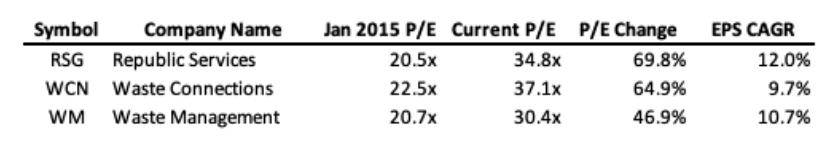

What’s been particularly interesting is how valuation multiples for the majors have steadily expanded over time, creating a powerful tailwind for returns (see image below on 2015 earnings multiples versus 2025). The market has rewarded their scale, predictability, improved margins, and balance sheets with progressively higher multiples, making the passage of time almost as important a contributor as earnings growth. But it also raises the question of how much room is left for further multiple expansion. When valuations are already elevated relative to history, it becomes harder to rely on them as a consistent driver of returns. Instead, you wonder whether multiples might ultimately normalize and turn to a headwind not tailwind, placing greater emphasis on underlying execution and cash flow durability, which these businesses surely have.

M&A

M&A is rife in the space and ultimately functions as a strategic tool that allows management teams to reshape their competitive position more quickly than organic growth alone would permit. When executed well, it lets companies consolidate fragmented markets, acquire capabilities they don’t currently possess, or accelerate entry into adjacent categories where the economics are more favourable.

I do not foresee a change in M&A strategy from the waste majors who seem to be broadening their scope through acquisitions of diversified services. In the past, waste companies just used to buy other waste firms (see Brad Jacobs @ UWS & Ron Mittelstaedt @ WCN) but now we’re seeing them venture into hazardous waste companies and specialty waste companies to diversify their portfolios. A few examples would be Republic buying out U.S. Ecology ($2.8bn, 14x EBITDA), Waste Management buying out Stericycle ($7.2bn, 13x), Clean Harbor & HEPACO ($400mn, 11x), and Secure’s forced divestiture of Tervita assets to WCN (C$1.1bn, 7.5x ). From what I read most of the smaller tuck-ins are taking place in the United States South East, SW & MW. And of course, internally these waste majors are improving margins through price/volume improvements. While in the costly Northeast there is a push for using rail to move waste.

These companies clearly possess enduring competitive advantages inherent in their business models (i.e., economics resembles that of a natural monopoly). They operate with scale that compounds efficiency, sustain pricing power, and distribution networks that create formidable barriers to entry. It’s no wonder they’ve been able to compound earnings for long periods of time. The M&A pipeline remains strong as well, giving management teams yet another lever to deepen the moat and grow earnings. Altogether, it paints a picture of businesses built to compound steadily, supported by both structural tailwinds and disciplined execution.